The “most active, best funded and well connected” relief organization dedicated to helping ethnic Germans immigrate to Canada after the Second World War was the Canadian Lutheran World Relief (CLWR).[1] Between 1951 and 1957, it assisted some 18,500 refugees, almost all German Lutherans. This was more than all other Canadian relief agencies combined during this period—indeed, more than any other voluntary agency in the world between 1952 and 1954, accounting for 13 percent of Canada’s intact of German immigrants.[2] These statistics make clear just how influential CLWR was on the postwar ethnic German immigration landscape. For this reason, no exploration into ethnic German immigration to Canada would be complete without examining this agency.

As early as 1947, however, CLWR leaders realized that aid was not a long-term solution and that efforts should be directed toward resettling ethnic Germans in Canada. As Lutheran churchman and scholar Norman Threinen noted, “the work of the CLWR … is what its first president called ‘helping the needy and homeless to find new homes and help themselves.’”[7] Unfortunately, this task was complicated by the limitations of the International Refugee Organization (IRO), which was established in 1946 to assist refugees and Displaced Persons (DPs) and resettle those who “for valid reasons” could not return to their countries of origin.[8] Most ethnic Germans “had no rights under the IRO. They were denied access to IRO camps. They could not leave Germany or cross an international boundary. They were not entitled to the same food rations of the eligible D.P.’s.”[9] Nonetheless, thousands of these ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe (those the Hitler government referred to as Volksdeutsche) were eligible to immigrate to Canada. (German citizens, whom the Hitler government called Reichsdeutsche, were not eligible for immigration to Canada until later.) CLWR stepped in to fill this gap in service, enabling German refugees to be processed in Europe and then conveyed by ship to Canada.[10]

This was a daunting task. In Herzer’s closing remarks at a September 26, 1947, CLWR meeting, he noted that after two long months of hard work only fifty refugee applications had been processed. This was, in his blunt assessment, “very depressing.” Christian civilization had never experienced such a catastrophe and that “the magnitude of the problem is likely to overwhelm us.” Despite this, Herzer kept his eyes on the mission and affirmed confidently: “You, and we, are their angels in carrying out this work and I am sure the good Lord will give us strength to carry out this work since the one hope which these hopeless ones have in the world to-day is you of C.L.W.R.” [11]

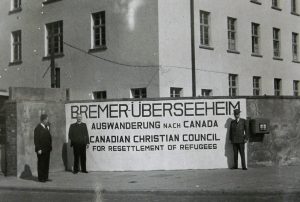

As CLWR Executive Secretary Monk remembered it later, “the real breakthrough in removing the roadblock to resettling German ethnic refugees … to Canada came at a meeting in Ottawa on June 23, 1947.” It was during this meeting that T.O.F. Herzer, CLWR’s first Treasurer, successfully petitioned for the creation of the Canadian Christian Council for Resettlement of Refugees (CCCRR), an ecumenical partnership of faith-based agencies, including CLWR, the Catholic Immigrant Aid Society, German Baptist Colonization and Immigration Society, Latvian Relief Fund of Canada, Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization, and the Sudetan Committee. This organization would be dedicated to helping ethnic Germans get to Canada.[12] The three objectives of the CCCRR were:

1. To be an umbrella organization for the participating members in areas such as administration, finances and dealing with transportation companies.

2. To be the vehicle for negotiation with Government re immigration policy and procedures (including later discussions with the Department of Labour).

3. To operate a processing/staging camp in Germany.[13]

The CLWR assistance to ethnic German refugees lasted from 1947 to 1960, during which time “a total of 20,845 Refugees and Displaced Persons had come to Canada because of the efforts, including travel loan assistance, of CLWR.”[17] Initially these “immigration schemes” (as they were called) were limited to close relatives of German-Canadian families. As Herzer noted to his colleagues, these refugees were “primarily the concern of the Lutherans in Western Canada, because among them are our relatives.”[18] Soon, though, efforts were expanded to other ethnic German refugees through diverse sponsorship programs. Chief among these were the various labour schemes, focused on importing manual labour, based on demand in the Canadian labour market, which varied from farming to mining.[19] In fact, it was the success of the CLWR in executing these schemes that earned them their good reputation among Department of Immigration and Labour officials.[20] As historian Ronald Schmalz explained:

Essential to the success of the CLWR’s resettlement program was its ability to place immigrants…. Because of its excellent record of placements, immigration authorities permitted the CLWR to forward workers and families without specific guarantees of employment. This concession greatly facilitated the flow of CLWR cases to Canada. In addition to pure placement work, the Lutheran network of churches, immigration and welfare agencies provided a host of other services to newcomers such a reception work at ports of entry and final destinations, welfare relief (especially during the tough winters of 1951-52 and 1953-54), counselling, loan and settlement investigations and employer-immigrant relations. These services gave the church programs an enviable reputation among prospective emigrants in Germany.[21]

In other words, CLWR’s superior performance in facilitating ethnic German immigration to Canada afforded the agency more opportunities to bring even more individuals and families over. One prominent labour scheme brought German immigrants to Canada to work as labourers in the sugar beet harvests of southern Alberta. This program “provided ready-made employment and accommodation, with responsibility for placement and much of the cost of transportation borne by the Canadian Department of Labour. Thus, large groups of people could be moved under the sponsorship of CLWR with a minimum of cost.”[22] Though this was advantageous to CLWR, Executive Director Monk expressed some concern in a meeting on September 14, 1948, noting that CLWR risked becoming a de facto “labour agency,” which was neither the intention or goal.[23]

Despite the success of many of these initiatives, the days of the CLWR helping ethnic Germans immigrate to Canada were numbered. Late in the year 1954, the Deputy Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Laval Fortier, held a meeting with various voluntary immigration agencies, such as the CLWR, at which he suggested that they should back away from the pre-selection of immigrants overseas and instead focus their resources on integration programs.[24] Those in positions of authority among the CLWR knew their immigration program days were nearly over and so by “1956 the emphasis for CLWR had shifted entirely to the movement of relatives, dependents and nominated persons.” In 1959 “the right of Voluntary Agencies to agency-sponsor persons who wanted to come to Canada and who did not have relatives to apply for them was suspended,” and by the end of the year 1960, CLWR’s immigration operations had effectively ceased.[25] Thus, the era of large-scale ethnic German immigration to Canada was over after thirteen long and successful years.

[1] Ronald E. Schmalz, “Former Enemies Come to Canada: Ottawa and the Postwar German Immigration Boom, 1951-57” (University of Ottawa, 2000), 206-07, http://www.ruor.uottawa.ca/handle/10393/9430.

[2] Schmalz, “Former Enemies Come to Canada,” 206-07.

[3] Schmalz, “Former Enemies Come to Canada,” 207.

[4] Clifton L. Monk, “Canadian Lutheran World Relief: A View from the Inside to October 31, 1961” (Winnipeg, Manitoba, 1990), 9.

[5] Ibid., 7.

[6] Ibid., 29.

[7] Norman J. Threinen, “Canadian Lutheran Response to the Challenges of Post-World War II Immigration” (St. Louis, 1978), 8.

[8] “International Refugee Organization,” International Organization 1, no. 1 (1947): 137. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2703532.

[9] Threinen, “Canadian Lutheran Response,” 4, 6.

[10] Threinen, “Canadian Lutheran Response,” 8.

[11] Public Archives Canada, “Mr. Herzer’s Closing Remarks at the C.L.W.R. Meeting,” September 25, 1947, fig. 510, MG 28V 120, Library and Archives Canada, http://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1390.

[12] Monk, “Canadian Lutheran World Relief,” 18-19; Schmalz, “Former Enemies Come to Canada,” 206.

[13] Monk, “Canadian Lutheran World Relief,” 19.

[14] Ibid., 19-20.

[15] Ibid., 20. Part of the reason the CCCRR was given the Beaverbrae was the issue of conflict between ethnic groups on International Refugee Organization ships.

[16] Public Archives Canada, “Report of Executive Secretary to C.L.W.R. Executive Meeting,” September 14, 1948, fig. 531, MG 28V 120, Library and Archives Canada, http://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1390.

[17] Monk, “Canadian Lutheran World Relief,” 28.

[18] Schmalz, “Former Enemies Come to Canada,” 207-08; CLWR, “Canadian Lutheran World Relief Fonds: H-1390,” fig. 508, Library and Archives Canada, accessed February 9, 2018, http://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1390.

[19] Threinen, “Canadian Lutheran Response,” 13; Norman J. Threinen, A Religious-Cultural Mosaic: A History of Lutherans in Canada (Vulcan, Alta: Today’s Reformation Press Incorporated, 2006), 141.

[20] Schmalz, “Former Enemies Come to Canada,” 207-08; Public Archives Canada, “Minutes of Executive Meeting of Canadian Lutheran World Relief,” February 5, 1948, fig. 516, MG 28V 120, Library and Archives Canada, http://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1390.

[21] Schmalz, “Former Enemies Come to Canada,” 209–10.

[22] Threinen, “Canadian Lutheran Response,” 16.

[23] Public Archives Canada, “Report of Executive Secretary,” September 14, 1948, fig. 532, MG 28V 120, Library and Archives Canada, http://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1390.

[24] Monk, “Canadian Lutheran World Relief,” 27. Monk claims that this suggestion was the result of pressure put upon the federal department by a “‘secular agency’” which had a problem with the concept of churches being involved in the selection process of immigrants.

[25] Ibid., 28.