“Working With Undergraduate Students in Local History Research: Placing Memory in High River,”

Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University

Roundtable: “History, Memory, and Community-Based Participatory Research in an Undergraduate History Program”

Conference: Conference on Faith & History 2016 Professional Conference, Virginia Beach, VA, October 22, 2016

First of all, I would like to thank Program Chair Beth Allison Barr and Conference Coordinator Josh McMullen, along with all those working with them, for including us in this CFH conference here at Regent University.

Our roundtable is entitled “History, Memory, and Community-Based Participatory Research in an Undergraduate History Program.” My name is Kyle Jantzen. I’m the Program Chair for history at Ambrose University in Calgary, Canada. With me today is my colleague Ken Draper, Professor of History, and one of our students, Roland Weisbrot. Together we would like to engage in a kind of reflection on practice related to our recent (indeed, not quite completed) departmental research project, “Placing Memory in High River’s Built Environment.” I’ll begin with an account of this project as a work of applied research in the context of our undergraduate History curriculum. Ken will follow with an analysis of the intersection of oral history, memory studies, and the meaning of places and spaces in the Town of High River. Roland will then describe his experience of the project as a student, and I will close with some thoughts about the value of university-community partnership and the impact of applied research projects like “Placing Memory” on faculty teaching and research.

Placing Memory in High River’s Built Environment

“Placing Memory in High River’s Built Environment” is a community-based participatory research project funded in part through a grant from the Alberta Historical Resources Foundation Heritage Preservation Partnership Program. In many respects, the project owes its existence to significant pedagogical changes in our undergraduate history program at Ambrose. Over the past two years, we have been engaged in a cyclical program review for our accreditation body, Campus Alberta Quality Council. As we assessed the strengths and weaknesses of our history program, my colleagues and I decided to re-centre our program not on geographical or chronological areas of study, but around historical thinking, methodology, skill development, public history, and applied research. Practically, what it meant for us and for our students was the creation of a new set of history core requirements centred around 1) two first-year world history survey courses, 2) a second-year methodology course, 3) a third-year public history course, 4) a third-year applied research course, and 5) a senior independent research project or practicum.

The third of these requirements—Applied Research in History—is a team-based, project-based course in which the students and I partner with local museums, historical sites, or other community groups to tackle small-scale research projects. We offer our faculty expertise and student research energy to help produce works of public history. Along the way, the students gain hands-on experience and regular mentoring in real-world historical research.

This is not unique. Indeed, it represents some of the current best practices in history undergraduate education, such as Stanley Katz and James Grossmann’s 2008 report on history undergraduate education for the Teagle Foundation, in which they advocate greater attention to public history, “taking advantage of local resources and explorations of local culture” and “training students to organize and present history to the general public.”[1] The other important recommendation relating to undergraduate programs stresses the positive impact of “hands on” education in history:

Since historical skills are an essential component of the history major, departments should ensure that all history majors have the opportunity to “do” history. History majors should have the opportunity to take some seminars in which reading primary sources and writing are important components of the course. Information literacy and familiarity with new media have become essential. History majors should also have some introduction to historical methods through seminars, explicit methodology courses, and/or thesis writing. … [T]he major should also include some engagement with local culture, enabling students to engage the materiality of historical learning. Collaborative work, increasingly the norm in other disciplines and in most occupations, should have a place in the major curriculum.[2]

Other recent studies, such as Michael J. Galgano’s work for the American Historical Association and various curriculum tuning projects in Europe and North America, echo the Katz and Grossman findings.[3] It is important to note that it would have been impossible for us to adopt this new pedagogical approach without Ken’s expertise and experience in both oral history and museum studies. The “Placing Memory” project was our first effort at such a team-based, project-based departmental research project. It involved both our Applied Research in History course and our Public History course and set the pattern for what we are continuing to do this year and in years to come.

If the adoption of a new skills-based, research-oriented, public-history friendly curriculum was one factor behind the “Placing Memory” project, the other was my ongoing role as chair of the Town of High River’s Heritage Advisory Board. This board was created six or seven years ago to assist town staff and external consultants in the completion of several Heritage Inventory Projects. These projects are funded in part by Alberta Culture, a provincial government department, and their purpose is to identify, assess, recommend, and promote worthy properties for designation as municipal historic resources. One day, in the course of our regular Heritage Advisory Board meetings, some of my fellow board members expressed a longing to do more than just work on these Heritage Inventory Projects—to do more to foster a sense of historical awareness in High River. I offered to facilitate a local oral history project, and their response was enthusiastic. This meant we had at least a handful of local volunteers to start with. Importantly, we also knew we would have a willing partner in our local museum, the Museum of the Highwood, whose director and curator, Irene Kerr, also sits on this Heritage Advisory Board.

As I worked with both Ken and Irene, the project took shape. From a theoretical standpoint, it was natural to employ a community-based, participatory research methodology. As many of you will know, what this means is that members of the community are active participants in research directed back into the community itself. This involves shared authority, shared expertise, shared decision-making, and shared ownership of the products of research. This has unfolded largely through our project steering committee, comprised of one faculty member (me), one Ambrose student, Irene Kerr from the Museum, and about six other members of the High River community, many of them from the Heritage Advisory Board. By linking the vast local knowledge of community members with the expertise of Irene and myself and the perspective of the students, we worked collaboratively to set goals for the project, identify important local sites of memory, as well as potential interviewers and interviewees, frame interview questions, and provide initial feedback on early interview results. The steering committee also critiqued the work of Ambrose history students and helped draw historical meaning from the research data we collected. When the steering committee resumes meeting a little later in the project, it will review drafts of the project report and historical findings, and give advice on how we can best disseminate the results of this research in the local community.

From a practical standpoint, it was natural for the project to revolve around oral history as a means to access local memory and knowledge about the meaning of various important places and spaces in High River, since this would dovetail with our existing work on the Heritage Inventory Projects. One year into the project, seven Ambrose history students and four volunteer interviewers from High River have completed 28 interviews with 38 interview participants totaling over 37 hours. Over half of these interviews (16) have been transcribed.

At this point, Ken Draper will explain our work in oral history, and memory and place, and some of the early results of the research in High River.

[Ken Draper – “Memory and Place in High River”]

[Roland Weisbrot – “Placing Memory in High River, An Oral History Project:

A Student’s Reflection”]

I would like to add a few thoughts about two other issues: the benefits of the university-community-museum partnership, and the impact of our project on faculty research and teaching. (Much of this is drawn from earlier presentations to the Organization of Military Museums of Canada and the Alberta Museums Association.)

The University-Community-Museum Partnership

The strength of the “Placing Memory” project is the partnership between the Ambrose University History program, the Museum of the Highwood, and members of the High River Heritage Advisory Board, who participated as project volunteers. Without the Museum of the Highwood, this would not have been possible. I want to identify six aspects of the museum side of our partnership, which I hope will stimulate our thinking about both the assets museums have to offer and the benefits museums can receive from projects like ours.

Credibility

The Museum of the Highwood is an important local institution, and the chief repository and interpretation centre for local history. Its recent exhibits have touched on subjects like the local history of television and film production, of the local business district, and of the place of music in the community. The museum offers regular outreach programs, works with school groups, and hosts community events, including an annual historic homes tour. Its director writes a weekly column in the local newspaper, usually highlighting an image from the museum’s photo archive. Because Ambrose is a newer university from Calgary, we have little profile in High River, which lies just outside the city. In order to engage in research in the community, the credibility we gain from our partnership with the Museum of the Highwood has been a valuable asset. It has opened doors into the community, not least through its relationship with the local media.

Relationships

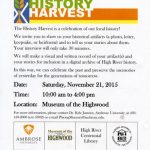

Related to the asset of credibility has been the asset of the Museum’s relationships with community members. The Museum of the Highwood has a broad network of contacts in and around High River, and maintains these relationships in part through regular e-mails and an active presence on social media. Because of our partnership, the “Placing Memory” project has received periodic promotion. This was particularly important for the History Harvest event we held in November 2015.

Space

This leads to yet another asset our partners at the Museum of the Highwood brought to the project: space. The Museum was a safe and welcoming place in which to hold our History Harvest event, collecting interesting research data on objects of memory. In the latter phase of our project, the Museum will also serve as the chief location for public events, including planned public lectures, the unveiling of a virtual exhibit, and the planned creation of a museum exhibit.

Research

Research was another key to the partnership between the university and the museum. Irene Kerr at the Museum of the Highwood opened her archive to my university students. She offered training in archival research methods, shared her own museum research experiences with the students, and arranged for one of her research volunteers to help our students search the museum’s extensive photo archive. As a result, Ambrose students invested over 75 hours into background archival research and photo identification and scanning, gaining valuable experience and gathering useful contextual material into which to locate the oral history interviews they conducted.

Training

As already mentioned, the Museum of the Highwood served as a place of training for university students engaged in the “Placing Memory” project. However, as we historians have trained local volunteers to conduct oral history interviews and provided instruction into the relationship between history and memory, and we have worked with the local steering committee to drive this community-based participatory research project, as we have involved upwards of 50 community members in one aspect or another of the “Placing Memory” project, the Museum also stands to gain a pool of trained volunteers and historically informed citizens it can mobilize for future museum projects. The “Placing Memory” project has stirred local interest in local history, and the Museum should benefit from that.

Content

As the students, local volunteers, museum staff and university historians work together on the “Placing Memory” project, we are producing significant historical resources for the Museum. Copies of all the oral history interviews (both audio and transcripts) will be deposited with the Museum for addition to its collection. (This is particularly significant in the case of the Museum of the Highwood, which lost its oral history collection in the 2013 flood.) Similarly, as members of Ambrose University complete the project, we are creating virtual exhibits relating to both places of memory and objects of memory. These exhibits will be linked to the Museum of the Highwood website, adding to their virtual exhibition offerings.

Faculty Research and Teaching

Getting the “Placing Memory” project up and running (and connecting it to the Applied Research course) involved a great deal of work: conceiving the project, partnering with the Museum, applying for funding, working through the ethical review process, engaging and training volunteers, securing background research material, scheduling interviews, meeting with the steering committee, convincing students to work outside a normal class schedule, and guiding them individually and as a group. As a course, it was both unconventional and unpredictable—while there was a general plan, as a real-world research project, it took on a life of its own, with the usual stops and starts and uneven workload of any research project. Assessing student work involved evaluating contributions that didn’t often eventuate in completed works of history.

Moreover, because the “Placing Memory” project was larger in scope than the Applied Research course, effectively, I took on a new research project. Assuming we continue to do these kinds of small departmental research projects over the coming years, this means that—just as I and my colleagues are generalists as teachers in a smaller history program—we are becoming research generalists as well, focused not only on our primary (personal) research projects but also on various short-term departmental projects in local history. I don’t particularly mind this, but it is worth noting that this is only possible because our university recognizes the Boyer model of research and scholarship, which includes a wide variety of scholarly activity, including joint research between professors and students.

Conclusion

We are excited about the way that the “Placing Memory” project has enlivened our history program, engaged students at a deeper level, and facilitated their development as researchers. Our own perception of this project was confirmed last spring when the external assessors in our cyclical program review—professors from two other universities—praised our work in applied research and public history as unique within our provincial university environment and recognized it as a significant contribution. We hope that our explanation of the project encourages others to take on this kind of pedagogy and engagement in local history, and welcome your questions and feedback at this time.

[1] Stanley N. Katz and James Grossman, “The History Major and Undergraduate Liberal Education: Report of the National History Center Working Group to the Teagle Foundation,” (report, 2008), 16-17, http://www.teaglefoundation.org/teagle/media/library/documents/learning/2008_nhc_whitepaper.pdf?ext=.pdf (accessed January 15, 2014).

[2] Ibid., 19-20.

[3] Michael J. Galgano, “Liberal Learning and the History Major,” (revised report, 2007), http://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/governance/divisions/teaching/liberal-learning-and-the-history-major (accessed January 10, 2014). See also AHA Teaching Division, “AHA History Tuning Project: History Discipline Core.” American Historical Association, 2013, http://www.historians.org/teaching-and-learning/current-projects/tuning/history-discipline-core; American Historical Association, “Tuning Resources.” American Historical Association, http://www.historians.org/teaching-and-learning/current-projects/tuning/tuning-resources.

[4] University of Nebraska-Lincoln History Department, “The History Harvest,” http://historyharvest.unl.edu/ (accessed October 13, 2016).