“Memory and Place in High River”

Ken Draper, Ambrose University

Roundtable: “History, Memory, and Community-Based Participatory Research in an Undergraduate History Program”

Conference: Conference on Faith & History 2016 Professional Conference, Virginia Beach, VA, October 22, 2016

Our narrators in this project provide a compelling picture of small-town postwar experience. Tucked in the foothills of the Rockies along the Highwood River … children range freely from town to farm to the park along river … local merchants are active in enhancing community life in a dynamic core area of about four blocks taking in the railway station, key businesses, hotels, post office, churches and the school. In 1960 the population was about 2000 and High River was the local business and administrative center for area farmers and ranchers.

In 2016 High River is a growing town of about 12,000, largely a bedroom community for Calgary about 40 minutes to the north. Shopping has moved from the core to the highway strip that is indistinguishable from that of any other western town. And yet High River continues to be committed to memories of that earlier time and what it represented. Iconic western landscapes and heritage buildings have made High River a regular set for movies and television, including a popular Canadian series Heartland, now in its 10th season. An active heritage advisory committee is designating historic building to preserve and protect the small town charm.

The importance of this heritage work was highlighted in the face of a major flood in 2013 which caused the evacuation of the entire town for several weeks. A natural disaster of this scale raised serious questions about how and what to rebuild. Some key heritage buildings were lost to the flood but much of that central business core has been restored and the town has invested in creating a pedestrian-friendly heritage look which speaks of memories of that post-war era.

This context seemed to provide an excellent opportunity for an oral history project to explore place and memory. Various threats to place, from the river and suburbanization, heightened questions about how memory functions to create a distinctive identity with a historic town feel. And at the same time, the Town portrays High River as an excellent place to live and invest, featuring all the amenities and services of a small city.

Kyle has described our efforts to redesign our history program with a focus on public history and research projects scaled to undergraduate participation. High River seemed to provide something of a laboratory to explore current directions emerging in public history variously labelled collective memory, social memory, cultural memory. Since the 1970s the work of Pierre Nora has sparked an interest in “sites of memory”. Beginning in France and focusing initially on sites of national commemoration, the identification and investigation sites of memory has gone international and expanded in scope to a wide variety of memorialization and memory projects. Maurice Halbwachs, whose work in the 1930s is widely seen as foundational to current thinking about memory, insisted that our individual memories are dependent on social frameworks. Halbwachs tells us our memories are made meaningful to us and are therefore retained because they conform to certain social conventions.

Oral historians have found this concept of collective memory very productive. The promise here is for oral history to tap into something beyond the individual’s, often faulty, memory. If individual memories are dependent on social frameworks of memory for “acts of recollection” (Halbwachs 1992, 38) then the oral historian should be able to uncover a collective memory in their analysis of multiple narrators.

Moreover, these social frameworks that enable memory include places. In explaining Halbwachs’ understanding of the relationship between place and memory Gérôme Truc underscores a dynamic relationship in which place anchors memory but memory gives meaning and structure to place.

Our memory is framed by spatial reference points: places, sites, buildings, and streets give us our bearings and enable us to anchor and order our memories. So the material alteration of these places can lead to the substantial modification of our memories, and even their disappearance. But we should not forget either that the collective memory, in turn, structures the space in which we live (Truc 2011, 148).

It was this interaction between place and memory that our oral history project set out to explore. To what degree has place, in this case the historic core of High River, anchored memory and what work does memory do to give meaning to these places? To explore the connections between “place” and “memory” the project posed these questions.

How does memory live in built environments?

How do built environments evoke memory?

What happens to memory as we lose historic buildings?

As Kyle has indicated, we used a community-based participatory research model and leaned heavily on local resources in High River to recruit participants and to help us think through some of our findings. This recruiting strategy meant that almost all of our narrators were longtime High River residents, often with ties to the Heritage Advisory Board. If we were wanting a representative sample of High River residents to test their appreciation of town’s historic charm, this would be the wrong strategy. However, this strategy did yield a fairly cohesive group of people with strong memories of High River in the post-World War 2 era that has allowed some analysis of a collective memory of place.

This memory, compiled from a number of accounts of the New Look, is remarkably consistent. There was a confessional tone in the storytelling indicating at once that experiences there were an important part of growing up in town, although one shouldn’t be particularly proud of having been there and participated. The New Look Café itself is gone, lost to fire some time ago, but the memories remain remarkably vivid. Perhaps some of this vividness relates to the fact they also conform to popular cultural memories of teenage sociability from this period. The after-school café and soda fountain are a powerful enough trope to ground collective memory even with the loss of place.

Memories of the historic business core may also benefit from a cultural memory of small businesses run by friendly and caring local proprietors. It was striking in reading through the oral history accounts how often experiences shopping in particular stores or of particular business people featured as significant experiences. Narrators were offered the opportunity to draw a map of their memories of the town and would recount stories business by business along a street. Stories of the unique skills of Bradley’s Saddlery attracting buyers from all over western Canada, of credit being extended or milk delivered to those in need, of owners who “you just felt good when you were around him.” The collective memory is quite particular to these places and people and yet all these businesses have closed and the shopping district has physically relocated. Despite this, memories of a cohesive and caring business community are clearly associated with the downtown core and focus attention on a social element to the shopping experience that transcends price and convenience. Cathy Couey captured something of this atmosphere in her memory of her Uncle’s clothing store.

… my Uncle Jack … had a clothing store. And what I remember there is he’d smoke cigars and you’d walk in and you know, I loved the smell of cigars but that smell was just comforting while you were there. That was just another social gathering spot. Kind of funny when we think about it now, everybody would take a brand new suit home and it smelled like cigars.

No one would tolerate taking home a smelly suit but here the memory speaks of a time when the social gathering was an essential part of commerce and this was what gave High River businesses their distinctive small-town character. And this character is in danger of being lost without attention to preserving the downtown core as a means of preserving a collective memory and passing this community value to those newly coming to High River to invest and live.

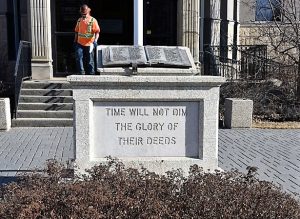

In her discussion of the cultural process of finding appropriate rituals of national mourning in Canada after the First World War, Denise Thompson found monuments in almost every city, town, or village which had experienced the loss and trauma of the war. Erected in prominent public places these cenotaphs, often borrowed a visual symbolic language from classical mythology and centered public rituals of remembrance and mourning. In contrast, post-World War 2 Canadians were more pragmatic, opting for “useful” memorials. A 1944 Gallup poll showed that “90 percent of those responding thought that tribute to the war dead would be most suitably expressed in the forms of playgrounds, hospitals, schools, and the like.”

High River participated in this “useful” approach to memorialization by creating a “memorial” centre as the hub of community life. Opened in 1948 and flourishing through the 1950s and 1960s, all of our oral history narrators had clear and typically positive memories of the Memorial Centre. The range of activities was quite remarkable. Wedding, graduations, school plays and concerts, community Christmas and New Year’s parties were all hosted here. Less happy were memories of school children lining up for their vaccine shots. The town library was located here, along with the Town offices. The Legion, a Canadian veterans group founded after World War 1, had rooms here as did the cadets, who had their shooting range in the basement. Boy scouts and girl guides met here and a national youth program called Teen Town had an office and held its Friday evening events in the auditorium. The range and significance of activities at the Memorial Centre are reflected in this comment from Deb Gardiner on raising her kids in High River.

And I hadn’t realized how much the Memorial Centre must have been part of our world, raising our children. My son and I were walking down to the Santa Claus parade a year or two ago with our granddaughters. And he said, “You know, we just about used to live in the Memorial Centre.”

I guess just that feeling of being in a community. You know, it was like you were connected. You would see people that were you know were all ages and I think I loved the Memorial Center too because it was big and we got to run, you know, even as little kids we were running around in there and I liked when the Remembrance Day service … we’d go in our Brownie uniform and you could feel the names of the fellows, the soldiers … it’s on the cenotaph … then you know you are going into something very … that was very serious.

For Lorna, the memory of community life and of connection is grounded in an intergenerational space where kids can run around and yet the solemnity of the memorial is preserved in the ritual of a Remembrance Day service, a uniform and physical contact with the names of the soldiers.

Connection to the Memorial Center promoted a wide range of memories that connected people to High River to a degree that, as Deb Gardiner speculated, may supersede the importance of the building itself.

I suspect the building isn’t the important part, it was the relationships of the people that were there. But the building housed it. It was like a bowl holding us all together.

As a place, the Memorial Centre was and continues to be a site of memory, and it is the collective memory of a tight community rather than any architectural refinements that make the place what it is.

So what did we learn from our oral history project?

By way of academic caveats, these are initial impressions and interpretations and the project is continuing and there are many more sites of memory that deserve attention. However, I think we can make a few suggestions.

Memory in High River is clearly placed and the Memorial Center, intentionally build as a site of memory, is perhaps the striking example of this. Intended to commemorate High River’s losses in two wars, it has done this and much more. The collective memory of the Memorial Center is of community life and connection, the critical hub of social interaction in the post-war years.

Memories of the New Look Café may suggest how collective memory is preserved with the loss of place. The New Look was lost to fire and so has stayed fixed in time as a period piece celebrating teenage sociability and carefully circumscribed transgression that might owe as much to “Happy Days” or Riverdale as to High River.

Perhaps the most interesting idea to emerge from this project is the importance of the compact downtown core and the potential of this to contribute to the present and future identity of the town. The collective memory of these places revealed a deep sense of community connection that is best captured by Bill Holmes, reflecting on growing up in this district.

I don’t know, I’m not going to say about every, about one particular building but one pleasant memory in my childhood was that the downtown section was inhabited. Every store had an apartment above it that was used by either the owner of the business or by his top clerk or something like that or just somebody in general. And living so close to downtown I used to spend a lot of time, I and my friends used to spend a lot of time going out visiting all these merchants and becoming friends with the people who lived upstairs, and we’d just go from one store to the next just to say hello and occasionally, you know, if we went to the butcher shop we might get a wiener, at the baker shop we might get a cookie or a donut or something, and then after that, you know after in the ‘70s and ‘80s the downtown was kind of abandoned at night because no one was around, no one lived upstairs anymore in these places. I missed that. It kept downtown a little bit vibrant there were always people on the streets.

Somehow I suspect that efforts to maintain a unique small town community identity in High River will be directly related to revitalizing and repopulating this downtown section of town.