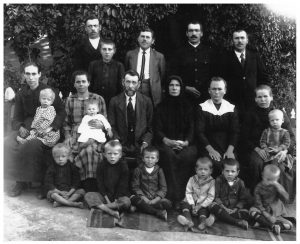

Monica Fercho’s parents came originally from Bessarabia, in southeastern Europe. Expelled from Bessarabia and relocated to Germany during the Second World War, they immigrated to Canada in 1950 and 1952. Monica uses her parents’ memorabilia to illustrate her family’s refugee experience. She begins by discussing a photograph of her father’s family, taken in the village of Manukbejewka in Bessarabia, just southwest of Chișinău, now the capital of Moldova.

Monica comments on the meaning of the picture to her:

You know, what I recognize is how bonded they were as a family and as a community. I had heard lots of stories growing up and having been back there, having experienced, you know, the stories I heard in my head and actually see where they lived. These are acacia trees—and the Germans that came from Germany—every acacia tree that you see in Romania, Ukraine—well the Moldavia-Ukraine area—were planted by the Germans. So now I have a new connection with what these are about. You know, they are dressed in their best and they were not wealthy. They came out on wagon trains. They didn’t have electricity, no plumbing in 1940. And this was a really big deal, this picture. So, for it to survive, it just explains a lot about who they were, you know? And what they are, and seeing people that I now grew up with look like them, right? You see yourself over and over in the family.

… It’s my only connection in some ways to some of the people in the picture. And my Opa was shot in 1945 when they were in West Prussia on the farm and the Russians were pushing through the front lines, and the rest of the family was literally escaping with their lives as he had gotten shot so he is buried there. So this is my only real memory of what he is and his family.

—————————————–

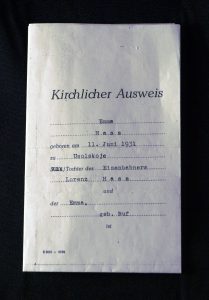

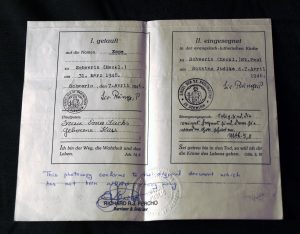

They escaped out of a train from Ukraine by Lenintal and they came through—she had quite an escape process and I don’t even remember all the details of all the places they were. But one of the places they ended up was in Schwerin, Mecklenburg. … So this was her baptism—I’m just seeing now. [Pointing to the document] This is her aunt, my Opa’s cousin’s wife, I believe, who ended up going to Cleveland in the States. That is her Patentante—her godmother. So this was 7th of April, 1946 and it was in St. Paulskirche Evangelical-Lutheran Church.

She was so proud of this, to have this event occur, that she studied for it—that she was a member of a church, a church that had a building, a Lutheran church that was still in existence. Because where she grew up under Stalinism they weren’t allowed to practice their faith. They were burying their Bibles in the ground, and anybody that was caught having a service even in the house was taken away. Like her grandfather was taken away never seen again. So I can just imagine this is why she has kept this. This is why it was so important: she was part of a community. It’s a beautiful church—red brick church that she had an identity with—that was safe at that moment. She was safe after the war. They lived in an apartment in that town, well city, I guess. First, they were in the armory, which I also saw right near the downtown. … So, she has memories, I believe, of safety—and that’s come across, as well as the accomplishment of the sense of community.

… She was with other family members—there was five families I think, so she was feeling, like, a sense of community. Her dad had already been drafted and—well at this point he was captured, actually—in the Gulag in Siberia. So, she was really connected with his family—his extended family.

… I recall her telling me that her and her other three siblings were all confirmed at the same event, and that they had to borrow clothes and shoes that were paper shoes because they had not anything to wear, to have for this event. It was very significant.

… She studied for and it was an accomplishment that meant a great deal. Because she also had very minimal education. … So this is something, I’m now recognizing … that she would have done from start to finish—which was you know, like everybody else had done—and graduated with no cutting corners.

—————————————–

Monica discusses the significance of having a physical object like the suitcase as a memory of her mother’s experience.

Well, I know at one point my mom said, “Just throw it out,” and I thought, “You know, I feel like it’s got—it’s symbolic of—it contains everything: their identity, what they had, what they could—what survived.” So I think it’s really important because as the years go on, other family members are not going to—they have no identification with the past physically because there was nothing brought, and this is sort of symbolic of that.

—————————————–

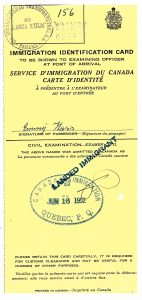

She was on the Arosa Kulm so there is a stamp on here showing that. And she came in 1952 and they left—so it shows the stamp of leaving from Bremen and coming in Deutschland or Germany to Quebec. There is a number 156, so I don’t know whether that meant that was the number of passenger she was, and it says “International Transportatora”—Oh, I think this was an Italian ship and then underneath it says “Panama.” I think that sort of rings a bell. It was a—I believe it wasn’t like a freighter and this is, “Immigration identification card to be shown to examining officer at port of arrival,” also in French, and there is her name, her signature. “Civil examination. The above was admitted to Canada as”—and, I guess, stamp “Landed Immigrant.” It could have had different stamps so this meant a huge thing. This was like a golden ticket to be able to come to this country. It was done on June 16, 1952, so landing in Quebec, and it was a very rough ride over. She was quite sick—she doesn’t remember much of even coming above board—and her birthday was June 11th, so this was the birthday present to come to this country and survive to be able to get here, and start a new life. It says, “Retain this card carefully. It is required for customs clearance and may be useful for a number of other purposes. Printed in Canada.” So, I am sure that with not knowing English even—that having learnt English—that was some of the reasons she kept it. … She would have held this close on that ten-day voyage over. Very close—and then crossing the country on the train.

—————————————–

This is a letter that was written by Reverend Clifton Monk, the Executive Secretary of Canadian Lutheran World Relief, who sponsored my mom and her siblings. So there was five siblings and my mom and my Oma—her mom. My Oma was a widow at this point because my Opa died in 1948 in the Gulag. He had a fifteen-year sentence and he never survived that. He starved to death. And so she came as a widow and brought the children—my mom was an adult at this point—and so this is almost a year later, well a year later, a year and a bit: September 18, 1953. And it’s a—I even might need help reading some of this but—it describes the amount of money: what she paid—what the church paid, what the Canadian government paid, and the amount that was owed by her brother and his wife and what was still owed by the family to pay back their fare. It started with—which I think was $460 to the church, $770 to the Canadian government, and then “davon bezahlt,” so they paid back $320 and $380. Then, $140 was still left to the church. It says, [reading German] I’m not sure what that means. Oh, that they also must owe that. Yeah, they must owe that.

… I see there’s $51 still owed by her other brother, Friedrich, and my mom has calculated out to make sure this is right; I just see this here in her writing. … the pastor that welcomed all the Lutheran World Relief refugees in Lethbridge was their pastor and he married my mom’s brother, my uncle Otto, and his wife, because they had just been married—they did not have a Lutheran marriage ceremony. They were just married on paper in the old country, so they actually had their formal ceremony conducted by that pastor, whose son now is now the president of Lutheran World Relief so it’s a “pay forward” moment of memory.

Finally, Monica reflects on the meaning of all the hard work the German refugees did to pay off their transport to Canada.

they paid everything back and they did it as quickly as possible because they wanted to be free—not just politically and religious, but just financially free. And that to them, I think, that meant that they were even more Canadian as a result that they owed nothing. I feel so beholden—I don’t know if that’s the right word—but grateful for this organization to have had the vision of what they did. I recognize—I don’t even think they realized what they were getting into, is what I’m recognizing, when they took this on. I believe not only did these people have trauma—my people had trauma when they came over, and it wasn’t really ever dealt with because there wasn’t an infrastructure to even understand it … and I’m really grateful to what all these volunteers and all this organization did to be able to allow all these families safe passage and to start a life which was truly safe and free politically, and socially, and financially, and contribute to the success of this country.